Last Thursday evening, the Florida legislature passed the most significant piece of public notice legislation in modern history.

Last Thursday evening, the Florida legislature passed the most significant piece of public notice legislation in modern history.

Sen. Ray Rodrigues’ (R-Fort Myers) SB402 makes Florida the first state in the country to significantly dilute the statutory requirement that notices must be published in print newspapers. But there’s a lot for the newspaper industry and residents of the state to like about the bill.

It’s certainly an improvement over the alternative, Rep. Randy Fine’s (R-Palm Bay) HB35, which would have moved public notice in the state from newspapers to government websites. Fine’s bill had passed the House by the time SB402 started picking up steam in the Senate.

In Indiana, future of notice arrives earlier than expected

By the time Indiana’s 2020 legislative session had ended, the Hoosier State Press Association promised leadership in both chambers it would begin working on a proposal outlining what notice in the state might look like in a future in which print newspapers were no longer its primary vehicle. Like other state press groups, HSPA would prefer to keep public notice in newspapers, where they belong. But the newspaper group was bowing to reality, according to Executive Director Steve Key. After mostly holding off 91 bad public notice bills in the past 21 legislative sessions, even erstwhile supporters in the legislature were telling Key it was time to look to the future.

By the time Indiana’s 2020 legislative session had ended, the Hoosier State Press Association promised leadership in both chambers it would begin working on a proposal outlining what notice in the state might look like in a future in which print newspapers were no longer its primary vehicle. Like other state press groups, HSPA would prefer to keep public notice in newspapers, where they belong. But the newspaper group was bowing to reality, according to Executive Director Steve Key. After mostly holding off 91 bad public notice bills in the past 21 legislative sessions, even erstwhile supporters in the legislature were telling Key it was time to look to the future.

It’s House vs Senate in Florida

Rep. Randy Fine’s (R-Palm Bay) House Bill 35 passed the Florida House on March 18 by a lopsided, almost party-line vote of 85-34. HB 35 would move all notice from newspapers to “publicly accessible websites and government access channels” — as a practical matter ending the long tradition of newspaper notice in the state.

Rep. Randy Fine’s (R-Palm Bay) House Bill 35 passed the Florida House on March 18 by a lopsided, almost party-line vote of 85-34. HB 35 would move all notice from newspapers to “publicly accessible websites and government access channels” — as a practical matter ending the long tradition of newspaper notice in the state.

But Rep. Fine’s bill was expected to pass the House, as it did in both 2019 and 2020. The question was always the Senate. Would HB35 stall in the upper chamber like it did the last two sessions?

After its bill passes, Guilford County loses interest in notifying citizens

Two nearly identical public notice bills have been introduced in North Carolina. Both bills would allow multiple counties, and the municipalities within those counties, to adopt ordinances authorizing them to move their notices from newspapers to the county website. H35 would apply to 11 counties and HB51 would impact 13 others.

Two nearly identical public notice bills have been introduced in North Carolina. Both bills would allow multiple counties, and the municipalities within those counties, to adopt ordinances authorizing them to move their notices from newspapers to the county website. H35 would apply to 11 counties and HB51 would impact 13 others.

Their Republican sponsors (one co-sponsor is a Democrat) structured the bills so oddly to avoid the almost-certain veto of Democratic Governor Roy Cooper. In North Carolina, the governor can’t veto legislation filed as a “local bill”, and local bills are limited to 14 counties.

Bills eliminating newspaper notice introduced in 10 states

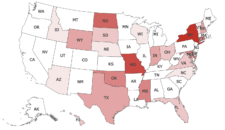

PNRC is presently tracking about 60 different public notice bills introduced in 22 states so far in 2021. (We categorize all legislation that has any impact on public notice laws — even a minor impact — as public notice bills.)

PNRC is presently tracking about 60 different public notice bills introduced in 22 states so far in 2021. (We categorize all legislation that has any impact on public notice laws — even a minor impact — as public notice bills.)

Legislators in ten of those states have introduced bills that would move all or a significant percentage of notice from newspapers to government websites.

[See 2021 public notice legislation map]

Doing it right: Providing third-party oversight

“Don’t let the fox guard the henhouse!” we warn legislators when they consider moving public notices from newspapers to government websites. There’s too much incentive for governments to hide notices if the responsibility for their publication is left solely to them, the argument goes. Newspapers are the independent publisher the public needs to ensure official notices actually see the light of day.

“Don’t let the fox guard the henhouse!” we warn legislators when they consider moving public notices from newspapers to government websites. There’s too much incentive for governments to hide notices if the responsibility for their publication is left solely to them, the argument goes. Newspapers are the independent publisher the public needs to ensure official notices actually see the light of day.

But the argument only works if newspapers guard the henhouse by providing oversight of the notices their government clients are statutorily required to publish.

NAM launches website linking statewide public notice sites

Newspaper Association Managers, Inc., a consortium of North American associations and non-profit groups representing the newspaper industry, recently launched a website aimed at promoting public notice in newspapers. PNRC is a NAM member.

Newspaper Association Managers, Inc., a consortium of North American associations and non-profit groups representing the newspaper industry, recently launched a website aimed at promoting public notice in newspapers. PNRC is a NAM member.

The website, USALegalNotice.com, pulls together links to the 47 statewide public notice sites operated by state press associations. The site allows the public to more easily access the latest public notice advertisements in different states, including foreclosures, public hearings, financial reports, ordinances and resolutions, and other important government proceedings.

Ballot measures, council vote nullified over notice issues

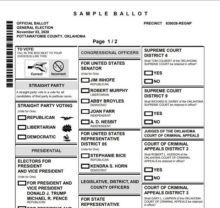

Five proposals to amend the City Charter of Tahlequah, Okla., were nullified last year as a result of the city’s failure to publish the city ballot in an official newspaper, according to the Tahlequah Daily Press.

Five proposals to amend the City Charter of Tahlequah, Okla., were nullified last year as a result of the city’s failure to publish the city ballot in an official newspaper, according to the Tahlequah Daily Press.

The mistake was discovered prior to the Nov. 3 election when a local resident contacted the Daily Press and alerted the paper to the missing ballots. The City Council later voted to keep the questions on the ballot to survey voters about the issues they raise.

Effort to end newspaper notice in Michigan falls short

Two months ago, Michigan appeared to be in grave danger of moving its notices from newspapers to government websites.

Two months ago, Michigan appeared to be in grave danger of moving its notices from newspapers to government websites.

As one of his final acts as a state legislator, now-former Michigan House Speaker Lee Chatfield, R-Levering (pictured at right), led the move to eliminate newspaper notice in the state. Chatfield, who would be term-limited out of office on Dec. 31, had pursued that goal since he was elected to the House six years earlier. He made it one of his priorities for the brief lame-duck session that followed the Nov. 3 election.

Public notice in grave danger in Michigan

Earlier the same week he visited the White House as part of Donald Trump’s ongoing effort to overturn the results of the presidential election, Michigan House Speaker Lee Chatfield, R-Levering (pictured at left) saw members of his caucus introduce a legislative package he hopes is the capstone of his half-decade project to move public notice in the state from newspapers to government websites.

Earlier the same week he visited the White House as part of Donald Trump’s ongoing effort to overturn the results of the presidential election, Michigan House Speaker Lee Chatfield, R-Levering (pictured at left) saw members of his caucus introduce a legislative package he hopes is the capstone of his half-decade project to move public notice in the state from newspapers to government websites.

It’s an unusual package of 105 separate bills that eliminate particular government notices — e.g., local government meetings, publication of new ordinances, etc. — spread throughout the state’s code. The bills are “tie-barred” to a single proposal, House Bill 6440, designed to serve as Michigan’s new general public notice statute. The tie-barred bills will only take effect if HB6440 passes.

Wyoming moves step closer to cutting newspaper notice

Wyoming’s joint Corporations, Elections & Political Subdivisions Committee voted narrowly last month to sponsor legislation in the 2021 session that would allow cities and counties to move notices for meeting minutes and employee salaries from newspapers to their own websites. The committee advanced the bill on a 7-6 vote after hearing testimony that it would save cash-strapped local governments $400,000 in annual expenditures. Six Republicans and the only Democrat on the committee voted in favor of the bill.

Wyoming’s joint Corporations, Elections & Political Subdivisions Committee voted narrowly last month to sponsor legislation in the 2021 session that would allow cities and counties to move notices for meeting minutes and employee salaries from newspapers to their own websites. The committee advanced the bill on a 7-6 vote after hearing testimony that it would save cash-strapped local governments $400,000 in annual expenditures. Six Republicans and the only Democrat on the committee voted in favor of the bill.